Josina Guess is a Sojourners assistant editor and a contributor to Bigger Than Bravery: Black Resilience and Reclamation in a Time of Pandemic. She lives on a small farm in Georgia with her husband, their children, and several animals. Read more of her work at JosinaGuess.com.

Posts By This Author

Displaced Residents Are Getting $10,000, but Not From the State

WEEDS GROW THROUGH a rusted wash pail in a thicket beside the University of Georgia’s West Parking Deck in Athens, Ga. Littered with the detritus of college life — beer cans, a condom wrapper, Styrofoam containers — this area, unlike the otherwise pristine campus, is neglected and uninviting. Walk in anyway. Look under brambles to find a bent scrap of aluminum roofing, a green Coca-Cola bottle, a cooking pot, and a plastic toy rifle. These objects, buried under vines and rotting logs, form the understory of what used to be a working-class African American neighborhood called Linnentown. Children would swing from grapevines to get across the creek. Now college students, high-rise dorms, and cars swirl above the 22 acres of the erased community. This patch of land, mostly buried under concrete and steel, was stolen from the Cherokee and Creek people first, but the people who remember the second forced removal are still alive. They can’t get their land back, but there is a growing movement for redress for communities like Linnentown.

From 1962 to 1966, the city of Athens used eminent domain under the Urban Renewal Act to force Linnentown residents out of their homes so that the University of Georgia could build three dormitories and a parking lot for their growing, mostly white, student body.

The children of Linnentown are in their 70s and 80s now. As a child, Hattie Thomas Whitehead ran from yard to yard with her playmates and sometimes snatched pears from Ms. Susie Ray’s tree. Christine Davis Johnson enjoyed pears, apples, and pomegranates from the trees in her own yard. They both remember the bulldozers running in the middle of the night, the intentional fires, and the sense of outrage when their parents and neighbors were forced to accept a pittance for their homes and land.

“It was a warm place to live,” remembered Johnson, who was 20 in 1963 when she and her newly widowed mother had to move. Johnson bore double grief that year from her father’s death and the loss of her childhood home. “No hate. My mother didn’t teach me hate,” Johnson said, as she thought about how her tight-knit community was torn asunder. “It’s gone, it’s over, don’t go back,” her mother would say to her. Against her mother’s advice, Johnson would sometimes drive through what used to be her neighborhood, just to remember.

The Revolution Will Be Dry

WHEN I WAS a student at Earlham College in Indiana, I co-hosted an alcohol-free dance party. Fry House, which was owned by the university, held a reputation for wild parties before we established it as Interfaith House in 1997. We — a group of religiously observant and spiritually curious undergrads — wanted to bring a new spirit into our house. I had been to enough drunken high school parties that I chose not to drink in college, other housemates had parents with alcoholism, and some abstained for religious reasons. We posted flyers, twisting a beer slogan into our hook: “Why ask why? Try Fry Dry!”

When the big night came, we pushed the furniture aside, laid out snacks, turned up the music, and swallowed our pride when only one person showed up.

This memory returned when I noticed with some surprise how Dry January, which has an app called “Try Dry,” has become a global movement. In 2013, the nonprofit Alcohol Concern (now “Alcohol Change UK”) invited people to abstain from alcohol in January; 4,000 people signed up. In 2022, 130,000 people signed up, with many more participating around the world. As alcohol-related deaths, especially among women, rose in that same period, Dry January began to take hold.

‘Sinéad O’Connor Saved Our Marriage’

AS AN INFANT, my son Malachi inserted an “el” sound into his cries. “Ah-La,” he wailed with outstretched arms. My husband Michael scooped up our boy and crooned Sinéad O’Connor’s lyrics, “All babies are born saying God’s name” (from “All Babies,” on the album Universal Mother, 1994).

As church-going Christians, we didn’t call God “Allah,” but we recognized it as the Islamic name for the Most Divine. We heard that name in our baby’s voice. But what strange lullaby was my husband singing to our child? “All babies are born out of great pain / Over and over, all born into great pain / All babies are crying / For no one remembers God’s name.”

I came of age to O’Connor’s 1990 album I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, belting out every word to the hit “Nothing Compares 2 U.” I stayed up late one night during 9th grade to watch O’Connor on S aturday Night Live. I was confused when she sang a cover of Bob Marley’s “War,” itself a rendition of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie’s 1963 speech to the U.N., then tore up a picture of Pope John Paul II. I did not know then that she was protesting years of rampant child sexual abuse largely ignored by the church. She wanted us to listen to the cries of children.

The Spiritual Satisfaction of Freely Gardening

“DO YOU MAKE any money from it?” a visitor asked as we walked behind my house, where goats, chickens, fruits, and vegetables grow among the weeds. I shook my head and laughed.

We entered the garden where my 74-year-old father knelt, breaking up soil with an old cultivating fork. He was planting spindly tomato plants I had started from seed and almost abandoned.

We don’t make money from it, but the garden is the place where my father cultivates joy. When I was a child, he poured water on rows of collards to wash away stressful days working for a Washington, D.C., nonprofit. Gardening restores his soul. These days, Dad splits his time between my parents’ home in Ohio and my home in rural Georgia, planting gardens in both places.

We don’t weigh the bushels of okra, cantaloupe, peppers, watermelon, and beans to see if they equal or surpass expenditures of time or money spent on Dad’s trips down South. Some work can’t be measured in dollars.

When the Curtain Closes in ‘TINA,’ Life Doesn't Imitate Art

BEFORE HE STEPS onstage as Ike Turner in TINA: The Tina Turner Musical, Garrett Turner (no relation) does a simple ritual: He swirls a wooden mallet along the rim of a Tibetan singing bowl. As the sound washes over him, he focuses on himself as Garrett, not Ike the musician and abusive ex-husband of the “Queen of Rock ’n’ Roll.” And he prays.

“Tina found Buddhism on her way to liberation from Ike, and it was something that Ike decried,” Garrett told me a few days after I saw him perform in Atlanta. Embracing something that Ike pushed away helps Garrett become Ike onstage while remaining Garrett within. With eight shows a week for the touring Broadway production, this spiritual practice helps Garrett draw a clear line between himself and the broken man he portrays.

Finding Our Stories in the Stuff We Cling To

“WHERE WILL THE Judaica go?” a friend asks Judith Helfand, in reference to the material objects of her faith. Helfand is an Ashkenazi Jewish documentarian who turns the camera on herself and her family to tell larger stories. Here, she’s telling a story of becoming a “new old mother” the year after her own mother dies. She takes a deep breath of her newborn daughter’s hair and turns to her friend, who is trying to help her store and organize the too many things in her New York apartment. “That is such a good question,” replies Helfand, who embraced motherhood by adopting at age 50. “It’s the age-old Jewish question,” she continues. “Once we left the desert we were like, s---, now we have to find places for our stuff!” She breaks into laughter, that special laugh of the sleep-deprived and overwhelmed new parent, and never answers her friend’s question directly.

Love & Stuff, a POV documentary available on PBS, based on Helfand’s shorter New York Times Op-Doc with the same name, is full of age-old questions about holding on and letting go. Love & Stuff doesn’t offer easy answers or quick fixes, instead revealing the struggles and choices we make in curating our living spaces.

Why Poet Lucille Clifton Is My Matron Saint

I was wrapping up some research in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University when I requested a box of Lucille Clifton’s personal writings. I had not come to study Clifton. I was researching anti-lynching activism in Georgia, specifically a 1936 lynching photograph. But by the end of the week, I began turning to Clifton’s personal writing as an oasis. “Resolve to try to fear less and trust more and be healthy,” she wrote in her red Writer’s Digest Daily Diary on December 31, 1979. Clifton was a published children’s book author, memoirist, activist, and the poet laureate of Maryland when she wrote those words. She was also 43, the same age I was that September day. Her body of work, which includes Two-Headed Woman and Blessing the Boats, crossed oceans, told family stories, and revealed both the sting of injustice and the heart of what’s holy.

The day after Clifton resolved to “fear less and trust more and be healthy,” she wrote in her journal that she returned to a house with “no central heat; bad plumbing; and foreclosure.” A few weeks later, the house was auctioned off to the highest bidder. She sat down and wrote something anyway.

Remembrance as Resistance

IN JULY, Lee Bennett Jr. stood at the podium of the Gaillard Center in downtown Charleston, S.C., as part of a three-day bicentenary commemoration of Denmark Vesey — a free Black man who had planned what could have been the largest organized resistance by enslaved people in U.S. history. Bennett brought both American history and personal history with him that day: The space where he spoke used to be his own neighborhood. There are some places where the veil between past and present feels especially thin.

The next day, Bennett offered me a tour of Mother Emanuel AME Church, where he is the historian. He spoke about Vesey, a founding member of Hampstead AME Church, established in 1818. In 1822, Vesey was arrested and executed, along with 34 others, for his plan to liberate the enslaved people of Charleston. Later that same year, a white mob destroyed Hampstead Church. By 1834, the city of Charleston made it illegal for Black congregations to meet, pushing the congregation to gather in secret until after the Civil War. In 1865, they came out of hiding and took the name Emanuel, “God with us.”

The Bible Verse bell hooks Shared With My Kids

When I met bell hooks three years ago, I had all four of my children in tow and I wasn’t sure what to say. A mutual friend arranged a short visit to her home. My heart was bursting with gratitude for all the ways hooks wove race, gender, class, faith, place, and love into her work. My mind was racing with ways to express some fraction of my appreciation and awe.

‘I Do Not Know How to Unclench Rage-Tight Teeth’

When I was in labor with my third child, my older sister was bewildered by my pain. As I walked the hall of our two-story row house in southwest Philadelphia, seeking moments of comfort between birth pool and bed, couch and floor, she said to me, “But, you’ve already done this before. Why is it so hard?”

“I haven’t birthed this baby!” I cried out to her. Then I settled into a deep silence, preparing myself for the next wave, the next earth-shaking moan.

Our souls are crying out this Advent of 2020. We want to call this season the coldest, these times the most hostile, this ache unbearable.

And it is true. We are saturated with the names of the dead, no longer shocked by callous leaders or the collective amnesia that refuses responsibility for ongoing systems of oppression.

Though history and our theology will remind us that empires fall, that pandemics cease, that justice will prevail, such awareness doesn’t diminish the pain of raw grief, this collective lament. We haven’t celebrated Christmas this year; how can we even begin?

I do not know how hope still shivers through my bones. I do not know how to unclench rage-tight teeth. I do not know how to look at this war-soaked, warming planet and believe that the Author of Peace is weeping and raging with us and making straight these deeply crooked and corrupt paths.

The Damage Done

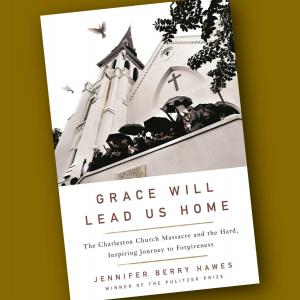

"AND THERE SAT a dark leather-bound Bible soaked in blood. A bullet had pierced its pages.”

The Bible belonged to Felicia Sanders, one of the five people to walk out of Mother Emanuel AME Church alive after a stranger who had been welcomed to a Bible study shot and killed Rev. Clementa Pinckney, Cynthia Hurd, Susie Jackson, Ethel Lance, Rev. DePayne Middleton-Doctor, Tywanza Sanders, Rev. Daniel L. Simmons, Rev. Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, and Myra Thompson.

The quote is from Jennifer Berry Hawes’ new book, Grace Will Lead Us Home: The Charleston Church Massacre and the Hard, Inspiring Journey to Forgiveness. With measured prose and journalistic excellence, this book rounds out the forgiveness and grace that have become synonymous with the Charleston massacre by exposing the outrage, isolation, and bumpy road of grief that followed the deaths.

Why I Brought My Children to the Montgomery Legacy Museum

MY THROAT STARTED to feel tight a few days before I went to Montgomery this April. I had been planning this pilgrimage to Alabama with my teen children for months but, as the days grew closer, I questioned my body’s ability to walk into the grief that was awaiting us at the Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

As a biracial African-American woman putting down roots in the rural South with my white husband and our four children, daily life can feel like an act of resistance. Every day we are faced with Confederate flags and memorials that celebrate an era and mindset that would have made our marriage and my equal ownership of our property a crime. But we love our home, the land, and our neighbors. We want, in the words of Gwendolyn Brooks, “to conduct [our] blooming in the noise and whip of the whirlwind.”

I was determined to bring my older children to the state of my birth, to take an unflinching look at our racist past and present, and to give them courage to walk the unfinished path toward justice. But still, I found it hard to breathe.

I gardened with a single-minded ferocity in the days before our trip, pulling weeds and digging up long taproots as though I could purge the evils from our land with my bare hands. Red dirt began to lodge deep beneath my nails and in the dry creases of my fingers, my forearms bore slashes from the thorny vines that whipped me as I tore them from the earth. There were flowers, thick with the hopeful scent of spring, trying to bloom beneath the tangle of weeds. I yanked and tore in every spare minute I had, stopping only when I noticed blood pouring from a deep slice on my right forefinger.

It felt right to come with dirty, bloodied hands into those sacred spaces in Montgomery.