Jeania Ree V. Moore is a writer, United Methodist deacon, and doctoral student in religious studies and African American studies at Yale University.

Posts By This Author

@BlackLiturgies Expresses the Sacred Truth of Black Life

FOR THE MILLENNIAL founder of a viral social media account, Cole Arthur Riley is surprisingly unplugged. “This is a fun fact that most people probably wouldn’t guess,” she told Sojourners in June, “but I actually don’t have a smartphone.”

Riley is the creator and curator of @BlackLiturgies, an Instagram profile and social media “space where Black spiritual words live in dignity, lament, rage, and liberation to the glory of God.” It is where, until this fall, she posted almost daily the liturgies she writes: Liturgies for Ma’Khia Bryant, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd. Prayers of remembrance for the Tulsa Race Massacre. Invocations for those living with chronic illness and those struggling with anxiety. @BlackLiturgies goes beyond the usual liturgical calendar of Advent, Christmas, Lent, Holy Week, and Easter, embedding that rotation within a larger grammar of spiritual expression for Black survival and thriving.

Riley’s liturgies look and circulate like memes, but trade humor for a holiness rooted in the embodied knowledge and sacred truth of Black life. The bricolage of written prayer, quotations, scriptures, poetry, and statements in white text on brown, green, and blue backgrounds gained thousands of likes and reposts within hours. If you are on social media, the images are likely familiar, but the person behind them, and her story, less so.

Whitewashing History Perpetuates Harm

GROWING UP, I read tons of historical fiction and often imagined the lives and times of my ancestors. My curiosity stemmed, in no small part, from my family, who dragged us to every available Black history and Black art museum. Whether visiting California’s first and only Black town, where my great-great-grandparents had bought land; making a pilgrimage to the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center during a family reunion; taking Black history bus tours; or hearing family stories from my grandmother and great-aunt, Black history was never far from our everyday lives.

Recently, technological developments and my growing archival research skills have enabled me to dig further into our family history. As DNA ancestry testing and digitized documents have become more widespread, I have been able to find graves and documents that could have been lost to history. The past, for me, has become even more close at hand as a crucial way of understanding the present.

Relating to the past in this way—an approach that resonates with Black families across the diaspora—stands in stark contrast to ongoing efforts to erase, distort, and lie about history.

I Found the Body of Christ Outside of Church

BACK IN FEBRUARY, I volunteered to drop off Lenten kits to members of the church I started attending several months earlier. Being relatively new to the city and congregation, having recently moved to the area, I was unfamiliar with most of the people on my list, as well as the neighborhoods, street names, apartment complexes, and long-term care facility indicating their residences. Assisting with Ash Wednesday before the pandemic might have been a fairly routine way of familiarizing myself with fellow parishioners—one of those innumerable little face-to-face encounters that slowly builds familiarity and trust in a church. This year, of course, there was none of that. My volunteer experience was isolated and individual. Ferrying containers of ashes, devotional booklets, and craft activities to people’s doorsteps and mailboxes, I saw no one, save the care facility receptionist.

This almost completely impersonal experience was also the most powerful ecclesial encounter I have had throughout the pandemic—the one that felt most like church.

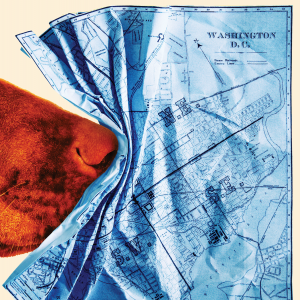

During the course of COVID-19’s restriction of in-person worship, I went inside a church only a handful of times. Once to say goodbye to the congregation I left when I moved from Washington, D.C.; once to get ordained in my hometown; twice to pick up liturgical kits at the church I started attending in my new city; and once to guest preach at this church, standing inside a sealed pulpit and preaching to a mostly empty sanctuary. All visits, except for the kit pick-ups, were livestreamed. I initially thought that being back inside a church after a forced separation would be some awe-inspiring faith moment—like coming home to God. What my experience this year taught me is that we never truly left. It sounds cliché, and maybe a bit untrue—after all, though the church is the body of Christ, the people and not the four walls, Zoom is not people. Virtual is just that: virtual. But that difference is precisely what I experienced when making Lenten deliveries. Driving to people’s homes, walking along their streets, encountering new neighborhoods (or rediscovering old ones, as I did upon realizing that people whose names I had seen only on screen were around the corner from me)—with each delivery, I felt like I was drawing invisible lines of connection between my residence and those of my fellow church members, my body and their bodies, locating us together in the world for the first time. It felt like communion.

‘Black Matters Are Spatial Matters'

WHEN I WAS 8 years old, in June 1998, three white supremacists lynched James Byrd Jr., a Black man in Jasper, Texas. After offering him a ride in their truck, they beat him, desecrated him, chained him to their vehicle, dragged him to his dismemberment and eventual death, and deposited parts of his body in front of a Black church to be found on Sunday morning. I remember hearing about the murder on the evening news and having a newly personal sense of the geography of racial terror. As a child living in California, I could not locate Jasper on a map, but its name, and Byrd’s, were forever fixed in my mind.

Earlier this year, I realized that my great-grandmother was around that same age when, in May 1918, white supremacists lynched Mary Turner and a dozen other Black people, including the baby they cut out of Turner’s abdomen. I wonder if my great-grandmother, as a child, heard the news, and how it affected her. In her case, the lynchings happened not three states but three hours from where she lived in Georgia. Unlike in Byrd’s case, there were no charges, arrests, trials, or convictions of the known and suspected murderers behind these lynchings. I wonder if and how the killings—and the impunity allowing the lynchers freedom of movement—shaped her sense of the landscape.

In Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle, geographer Katherine McKittrick writes that “Black matters are spatial matters.” McKittrick identifies the social production of space—how landscape is not a fixed background but is defined by relationships. Fugitivity, precarity, and possibilities of life and death are mapped realities that follow social relationships.

In Search of My Mother's Garden

THIS SPRING, MY mother and I did something we have not done together since I was in junior high school: a creative, collaborative liturgical project. Starting when I was about 4 years old, my mother and I would make Christmas cards each year to give to our family and friends. She provided the text, usually in the form of her own biblically and seasonally inspired poetry, and I, an avid drawer, would illustrate her words. We continued this tradition for more than 10 years.

When the church I now attend invited contributions for a crowd-sourced congregational Lenten devotional booklet this year, my mother came up with an idea. She was, as she wrote, “A mom inspired by a thought—as Paul wrote letters to his beloved children and friends in faith ... so could I write a letter to my daughter.” Following the model of the Pauline epistles, my mom wrote me a letter of spiritual encouragement and advice on navigating wilderness, a key feature of both Lent and life. I decided to respond and thank her with a letter of my own. Together, the individual expressions of our relationship became a communal project.

In contemplating our project, I see a creation whose significance is more than the sum of its parts, so to speak. The joint submission of correspondence between my mother and me is not simply a nostalgic return to a lapsed family tradition. Rather, it is a reflection of a profound theological aspect of our relationship: the cultivation of selves in the space of love.

The Problem With ‘Historic Firsts’

I FIND MYSELF thinking about the significance of “firsts,” the role of faith in the morality of the nation, and the place of race and gender in that project. Vice President Kamala Harris’ ascent to one of the highest seats of political power is historic, unprecedented, and awe-inspiring. Like Barack Obama before her, it is a first that has ushered in, for many, a renewed faith in the nation. Multiply the emotional impact of that first by whatever number captures the firestorm of the past four years, and that faith easily transforms into a belief that “morality” has been secured and that things are going to be, basically, okay.

This train of thought is, I believe, dangerous and wrong. I do not discount the feelings Harris evokes. The emotional impact of Harris’ election registers for me very personally as a Black woman. When I initially heard that Joe Biden and Kamala Harris had won the election, my first thought was exhilarated shock at Trump’s defeat. Then, as that fact sunk in, I realized that this outcome meant the election of a woman of color—a Black woman, a woman of South Asian descent—to the vice presidency of the United States. Weeks later, the words still seemed somewhat strange, as if my brain was having trouble wrapping itself around the reality. My inability to readily speak her new position reflects to me the depth of her significance, and the change it portends for how I and future generations of Black and brown girls and women will be able to envision and speak of ourselves. I pause, however, at the unexamined triumphal connections being made between Harris, morality, and political futures.

Rest Is Resistance, Too

WHAT IS REST and what does rest look like during a time of pandemic?

Over the past year, the multiple pandemics we have faced have upended many things, not least of which has been our language. “Essential” has been revealed to be simply another word for “disposable,” with “essential frontline workers” being those whose lives society deems expendable, not irreplaceable. “Safe” has been shown to be so shoddy, subjective, and circumscribed a reality in this country that protesting for Black lives in a pandemic is indeed safer than failing to protest at all. And “rest”—what is rest?

Many of us were struggling with healthy notions and practices of rest prior to COVID-19. Now? “Rest” seems both undefined and unattainable. Biblical images of rest have often been interpreted to emphasize separation, distance, and juxtaposition. For example, Jesus withdrawing from the crowds is often read as modeling rest distinct from the activity, the hubbub, the movement, the people. There is value in this reading of rest, particularly in how it spatially mediates self-care (thus, “retreats”). The thing about pandemics, however, lies in the pan- prefix denoting “all” or “every.” As safer-at-home policies and seemingly limitless racial violence make clear, whether facing COVID or white supremacy, withdrawal to elsewhere is not an option. So, what does rest mean when one cannot “retreat,” spatially or politically or otherwise?

When Calls Began for This Memorial's Removal, I Faltered

EARLIER THIS YEAR, Emancipation Memorial in my neighborhood of Lincoln Park in Washington, D.C., became the target of national protests and calls for removal. Erected to great fanfare in 1876, the memorial is not a Confederate monument but an homage to Black freedom built with the hard-earned dollars of former slaves. It commemorates a sacred moment in Black history, but does so with the racist imagery—and thus fictive narrative—of Abraham Lincoln dominating a crouching, half-dressed, emancipated Black man.

I resented Emancipation Memorial each time I passed by it, but when the calls began for its removal, I faltered. Learning its history several years ago as a monument fundraised by formerly enslaved Black people forged for me feelings of connection to it, even as I recoiled at its imagery. The meaning of “home” it carried as the landmark naming my D.C. neighborhood and church intensified in light of these feelings. My complicated response led me to reflect on another structure close to home for me that has yet to be dismantled.

Born Again Through Tactile Memory

LAST SUMMER, I started composting. What began as an economical exercise focused on reduction became, over time, a relationship based on generosity and gift. When COVID-19 interrupted my weekly routine of dropping off food scraps, I realized with a jolt that composting felt less like an act of frugality and more like bringing tribute. Unexpectedly, through composting, I had entered into relationship with the earth—and this was a recovery of something long forgotten. As Robin Wall Kimmerer urges us to remember inBraiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants, we exist in reciprocity with the more-than-human world.

This remembrance parallels a tactile memory I experienced last winter while running my hands through a bowl of dried black-eyed peas. The feel of the beans, almost like coins, merged with images of large, elementary numerals in my head and movement, like an abacus, from one side to another—a flash so quick and wordless I could not be sure. When it happened again a few months later, I remembered: This is how I learned to count. My grandmother—a foundational figure alive for my first 18 years—taught me to count with beans.

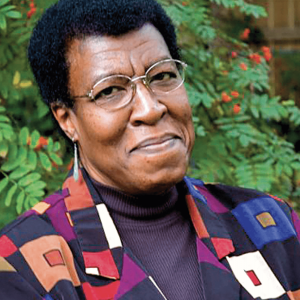

Misreading Octavia E. Butler's Survival Lessons

IN MARCH , I made my first, and hopefully last, “panic-buy” of the pandemic: three survivalist books that look more like they belong in a nuclear bunker than on my bookshelves amid the theology, poetry, and knitting patterns. My purchases were, however, inspired by my reading Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents, classics by the science fiction literary giant Octavia E. Butler (1947-2006).

In these novels, Lauren Olamina—a young, disabled black girl—survives the apocalypse and helps rebuild society with her knowledge of edible wild plants, her sheer will and bravery, and her newfound religion, Earthseed. Lauren’s ability to adapt, to change, is her route through unimaginable suffering and the bedrock of her faith.

Originally published in 1993 and 1998, respectively, Butler’s Parable books were reissued last year, highlighting their current resonance. Sower introduces us to the United States in 2024, a dystopia ravaged by global warming, capitalism, and violence. Slavery, misogyny—the witch-burning kind—homelessness, and addiction are rampant. Lauren’s community is secure as long as the walls that surround it stand; as she rightly senses, walls are wont to crumble. She launches a backup plan that offers a hard hope within relentless loss. Talents continues Lauren’s, and her daughter Asha’s, journeys over the coming decades as the U.S. faces rising terrorist Christian nationalism and the election of an ultraconservative president who wants to “make America great again.”

Finding Hope In ‘The New Dark Ages’

EARLIER THIS YEAR, I almost did not finish writing the sermon I was scheduled to preach at a special Martin Luther King Jr. Day Social Justice Shabbat service. Usually, I am able to bring sermons to a close without problem; this time, I struggled. Really struggled. Instead of focusing thematically on racism, poverty, war, or any number of issues King spoke out against, I had decided to preach on fear. I felt called to name fear as the root issue beneath so many others, something we struggle with individually and collectively. Fear of scarcity, fear of the unknown, fear of the “other”: the immigrant, the unarmed black person, the queer, the Sikh, the Muslim, the Jew, or the white person now encountering you in your queer, black, immigrant, brown, Muslim, Sikh, or Jewish body.

I found that once I started being honest about the fears we hold and the fears we face, I could barely turn the corner, in a manner of speaking, toward hope.

Eventually, I was able to theologically pivot my sermon and conclude positively. However, that experience of being spiritually stumped with writer’s block said more to me than any happy ending ever will. Rather than yielding answers, my sermon gave me questions, which continue to resonate in the midst of a global pandemic.

What Does Contemporary Lenten Fasting Look Like?

Today, the Reclaiming Jesus elders are again calling us to liberation in public witness, but through means other than a rousing church service and candlelit procession to the White House. This time, the journey moves through time (40+ days) rather than space, and the destination is not the presidential residence but something a bit closer to home, if more difficult to reach: our own souls.

Why Fasting Is Actually About Liberation

FOR MUCH OF my life I thought of Lent primarily as a season of personal piety, a self-contained period of reflection on individual sin and repentance. This penitential practice was limited in both scope and duration: It had little to do with others apart from me and God, and its impact did not extend beyond Easter. I approached a central component of Lent—the fast—like a trial, a test of willpower that pitted God against some “thing” I had given up, often a food (usually cheese or dessert). Much to my chagrin, in this personal test of will, God did not always win out. Overall, I was grateful and relieved each year when Lent ended.

Two years ago, things changed. As a dairy and meat aficionado who unexpectedly found herself a convert to vegetarianism and pondering veganism, I suddenly had a new relationship with chosen fasts. (The cause: Eating Animals, a book on factory farms written by Jonathan Safran Foer, collaborating with Jewish ethicist Aaron Gross. Read at your own dietary risk.) Vegetarianism helped me engage fasting as something internally motivated by ethical and spiritual concerns, rather than externally imposed. Participating in my church’s annual Daniel Fast later that year deepened this new experiential understanding. Based on Daniel 1 and featuring weekly 12-hour periods with no food, this fast helped me experience how fasting is not about willpower, but surrender. It taught me about hubris, humility, and moment-by-moment reliance upon God, which often involved other people.

Night At the Museum

TO ENTER THE main history galleries of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), you have to descend. A glass elevator carries you down through six centuries of history, dates written on walls like exposed strata in the earth. The past, we are reminded, lies not behind us but beneath us.

The weight of your passage and what lies ahead does not hit you until you step out of the elevator and emerge to the 1400s. You have arrived in a trans-Atlantic world as yet unmade, a geography not yet drawn by greed, suffering, and death. You will return to the surface and the present slowly, and only by walking the mile-and-a-half-long exhibition corridor on a winding route through slavery to an unsecured freedom.

No matter how many times I take this journey, it never becomes familiar.

The emotional shock of history is too great, contained in the thousands of everyday items on display: tiny, child-sized shackles; pieces of an excavated slave ship; an entire slave cabin, transplanted from South Carolina; a small silver box that held one man’s treasured possession, his free papers; Harriet Tubman’s lace shawl, given to her by Queen Victoria. Emmett Till’s casket.

NMAAHC, or the “Blacksonian,” as I like to call it, makes explicit what is sometimes only gestured to by other institutions: the sacredness of history.

Gun Violence Leaves Me Wordless

LIKE MANY PEOPLE, I have spoken out more times than I can count under the literal and metaphorical banner of “Silence Is Violence,” my voice growing louder and louder in the past several years.

Yet recently, on one matter, I found myself having fewer words, not more. Gun violence rendered me mute.

The death counts that rise in real time. The fact that before we have comprehended one shooting, another has occurred. The relativizing of value and shifting calculus of loss we have begun to accommodate this “new normal.” The reality—contrary to what one would think based on media attention and political rhetoric—that mass shootings account for less than 2 percent of U.S. gun violence (suicides, by contrast, account for nearly 66 percent).

50 Takes on the American Experience

THE WORD THAT comes to mind when considering American Journal: Fifty Poems for Our Time is gift. Edited by former U.S. Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith, this anthology of poems from 50 living American poets addresses the nation with generosity. In her introduction, Smith describes American Journal as “an offering” for us to expand, renew, or establish our relationship with poetry and each other. She writes that she loves poems because they invite her to “sit still, listen deeply, and imagine putting [herself] in someone else’s unfamiliar shoes.”

American Journal presents 50 different takes on the American experience: a school field trip (“The Field Trip,” by Ellen Bryant Voigt); war (“Personal Effects,” by Solmaz Sharif); the shouldering of inequity on young, brilliant lives (“Mighty Pawns,” by Major Jackson); addiction (“My Brother at 3 AM,” by Natalie Diaz); work (“Minimum Wage,” by Matthew Dickman); language (“Music from Childhood,” by John Yau); and hope (“For the Last American Buffalo,” by Steve Scafidi).

When Racism Pits Animal Justice Against Black Humanity

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 was one of the worst environmental justice disasters in modern U.S. history. It was also one of the first times that I, then a teenager, consciously connected animal justice and racial justice. Kanye West’s declaration “George Bush doesn’t care about black people” is often remembered as the statement on racism in Katrina, but another expression that needed no words circulated among black people in the hurricane’s immediate aftermath: a picture of pets being evacuated on an air-conditioned bus.

While black people were abandoned, dead, and dying on rooftops, corpses floating bloated in flooded streets, people’s pets were evacuated to safety.

Black people have long understood as racist the disparate treatment of nonhuman animals and black people. In 1855, Frederick Douglass wrote that “The bond-woman lives as a slave, and is left to die as a beast; often with fewer attentions than are paid to a favorite horse.

My Year of Reading X

SUMMER SIGNALS FREEDOM. If you are anything like me, two words in particular shimmer with the season’s promise of boundlessness: Summer reading.

At the beginning of Black History Month back in February, however, I decided to restrict my reading for this year. Some friends and I embarked on what I christened a “Year of Reading X”—a year of reading only, or mostly, books by black, Latinx, Asian, Indigenous, and other authors of color.

While recent discussions around the whiteness of the publishing industry and Western canon have motivated many to make racially aware reading commitments, exclusively reading black authors or authors of color is not novel. People of color have long been aware of the whiteness of the conventional literary world and have negotiated it accordingly, finding and creating our own spaces. What sparks my year of reading, then?

Why We Love (and Hate) to Be Counted

ON APRIL 1, 2020, the United States will hold its 24th national census, taking demographic stock of its population, some 330 million people in more than 140 million households. The census is one of the greatest equalizing forces in society, with a goal of counting each person living in the U.S. to apportion political representation through state and congressional redistricting and to allocate hundreds of billions of dollars in federal funding to states, counties, and communities. The census reflects the changing face of a nation.

Accordingly, the 2020 census will see several firsts: the first to ask about same-sex marriage, the first using an online method as the primary mode of response, and the first to request specific details on ethnic origins within racial categories such as “White” and “Black.”

Many embrace the census for the opportunity it presents to redefine our national portrait. Many fear and distrust it for the same reason.

The Trump administration has proposed reintroducing a question on citizenship status that has not been on the census since 1950. Its possible inclusion has raised outcry and constitutional challenges from multiple quarters claiming that a citizenship question could lead to significant underreporting from documented and undocumented immigrant communities. Although the U.S. Census Bureau promises that all census data is confidential and protected by law, many fear data could be shared with other government agencies to target immigrants, punish “sanctuary cities,” and more.

The New Transatlantic Slave Trade

THE YEAR 2019 marks 400 years since a boat carrying “20 and odd” enslaved Africans landed at Point Comfort in colonial Virginia. To commemorate this and other historic 1619 events, Virginia will host “American Evolution,” a yearlong celebration in which these events have been transmuted into national values. The arrival of enslaved Africans on American shores has become “diversity.”

Yet, last summer a West African immigrant was deported back to Africa to face slavery, in a transatlantic reversal of journeys that underscores the persistence of immorality in this involuntary passage.

On Aug. 22, Seyni Diagne, a 64-year-old immigrant battling kidney cancer and hepatitis B, was deported from Dulles International Airport in Virginia to his home country of Mauritania after 17 years in the U.S. There he faces enslavement through forced labor. Mauritania has one of the highest rates of slavery in the world, impacting more than 40,000 black Mauritanians.

The day following Diagne’s deportation was the International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition. The Commonwealth of Virginia chose to mark it by recognizing the first Africans in English North America.