When campus life shuttered in March to slow the spread of the coronavirus, more than 14 million students across the nation were forced to adapt to new routines. Campus lawns speckled with students gave way to uniform rows of faces on video calls. The now coined “Zoom fatigue” replaced “pulling an all-nighter” at the library.

While the pandemic has strained students from all academic disciplines, seminary and divinity students have felt unique pressure as they discern calls to enter positions and spaces of worship that may not resemble what they did before the virus took hold.

Four students shared with Sojourners what their studies look like amid the pandemic and how this moment is shaping their call.

Jordan Aspiras, Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary

Jordan Aspiras, a first-year student at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary in Illinois, sensed that her classes would move online in March. Her family back home in California’s Bay Area had started sheltering in place weeks earlier. Still, when she got word that she would need to vacate her dorm, she said it “felt more abrupt than expected.”

Now back at her family’s house on the West Coast, her 9 a.m. class has become a 7 a.m. Zoom class. It’s been a challenge, she said, as ministry is “such a relational degree.” She misses Garrett, especially the library.

“Our new normal is not quite fully developed yet,” she said.

But she said the moment has brought the Garrett community together in ways she didn’t expect. Since leaving campus, her phone has been flooded with texts from classmates and friends asking how she is doing.

“It has shown, I think, the true colors of Garrett,” she said. “People want to support each other.”

Aspiras plans to serve as a Navy chaplain after graduating from Garett. As a person of color and a woman, she said the diversity of the military is a draw for her.

“There are plenty of women serving in the military,” she said. “But you may not have that representation and support from a ministry side.”

Despite the stress of the present moment, she believes that she and her classmates will emerge as stronger faith leaders. Already, she said, young people are writing a new story for what the church will look like.

The post-pandemic church will require flexibility, she said. Even now, she is questioning whether we will need buildings or whether we even need to meet every Sunday to retain the value of our faith communities. She stressed that she does not advocate for uprooting everything, but she knows that an ability to adapt will be important in ministry positions.

“Ministers specifically are going to have this additional tool in their tool belt because we've had to make a lot of changes and take on a lot of leadership positions that maybe we weren't ready for,” she said.

Ashley Seng, Candler School of Theology

Ashley Seng, a second-year student at the Candler School of Theology, spoke with Sojourners after taking a class exam online.

“It was fine,” she said of the exam. “It just feels different to be doing it at home.”

Seng has been taking her courses online since March 23. She said class participation feels awkward on Zoom. Sometimes there will be audio feedback or two people will try to speak at the same time, unable to hear the other.

“So much of seminary and so much of the classes that I was in [are] about being together and learning from each other,” she said.

To aid students, Candler cut class time in half. But Seng still feels exhausted after signing off. She said it’s hard to believe that just a few months ago she was at school from 9:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. and then would go home to four hours of homework. Now after class, she shuts her computer and goes for a walk. Anything to not have to look at a screen, she said.

Seng enrolled at Candler to study chaplaincy. This March, she was finishing up a chaplaincy internship at a senior living facility in Atlanta when the facility stopped allowing visitors.

“I didn't get to give a proper goodbye to residents,” she said, “a lot of whom I had built deep relationships with over the course of the year.”

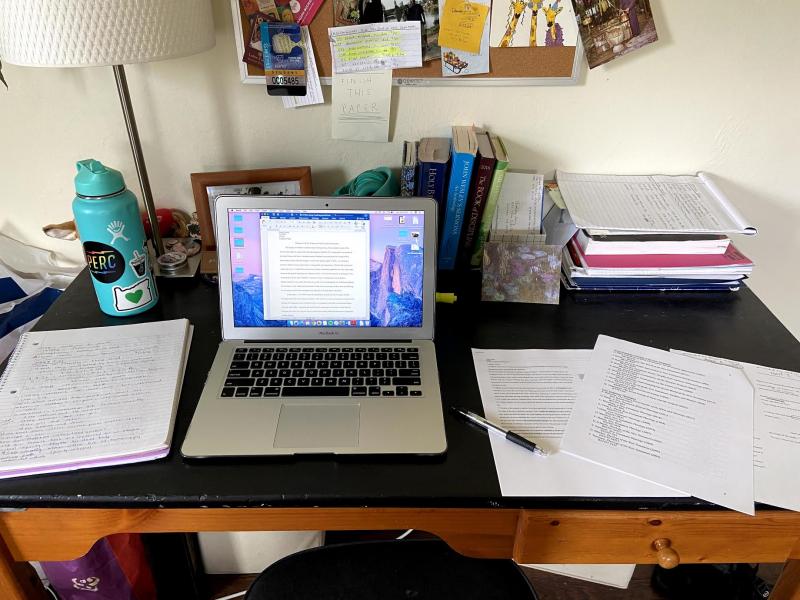

0.jpg

From her house, she now writes cards to the residents. Some days, she practices tele-chaplaincy, making phone calls to residents as many other chaplains across the nation are doing in the midst of the virus.

She said that while she is grateful for the technology that allows her to continue to interact with the residents, she worries what might be lost if it continues to be the prevailing method of communication.

“The way that I'm learning to be a chaplain comes from the physical presence and the space that you can create between two people,” she said. “And that, just for me, isn't fostered the same way over a phone.”

She had accepted a summer position in a clinical pastoral education program at a hospital in Atlanta, but learned recently that it has been canceled due to the virus. Now, she’ll complete the program after she graduates next spring.

She doesn’t know what chaplaincy will look like after the pandemic, but she said that she will be sad if it becomes something that happens remotely.

“I think that I will have to sit with my call and wonder where I am best fit,” she said.

Camille Loomis, Duke Divinity School

When Camille Loomis, a recent graduate of Duke Divinity School in Durham, N.C., thinks of her future in ministry, her mind goes to the Catholic priest in Germany who taped photographs of his congregants to the pews so that when he recorded Mass, he could look out and see their faces.

“He knew how important it was for him to recognize the personhood and the relationships that he had with all of his congregation,” she said. “So much so that for him, he needed to have their faces with him as he was worshipping.”

It is the “perfect image” for what the church should endeavor to be after the pandemic, she said. Not caught up in spreadsheets and budgets, though those are important, she said, but deeply invested in the relationships built.

Loomis spent three years teaching music in Mississippi before enrolling at Duke Divinity School. She said those years were spiritually formative for her. It was there that she was baptized for the first time as an adult in the church. And even though the church community she was a member of was not supportive of women in ministry, she said the members were very supportive of her and encouraged her to fulfill her call and vocation. At Duke, she said her call to ministry crystallized.

Now, as she prepares to leave Duke, she, like many others, is reflecting on the role of the church.

“A lot of folks are wondering what the job of the church is … and if there is a place for the church in times of dramatic upheaval when we can't all gather together,” she said. “But I think the churches that will come out on the other side with a clear commitment and a healthy congregation will be the ones that have already invested in relationships within their community [and] within their congregation.”

95917867_231884188093306_5017601595160920064_n.jpg

One thing that’s helped Loomis stay connected with others during this time is singing. Every Sunday, she and other members of the Duke Evensong Singers gather together on Zoom and sing hymns. It’s not the same, she said, but even just knowing that they’re “all together spiritually and singing at the same time” is something.

In the end, she said, "community flourishing" is what the church at its best embodies. And it’s the relationships that will bring people back together.

“The time apart from people I think has really made me realize how precious the practice of being together is” she said. “Christians embody an incarnational faith …we worship a God who came in body as Jesus and dwells with us as Emmanual, and there's nothing like being ... forced to be separate, to [make us] yearn for that closeness.”

Justala Simpson, Huntingdon College

For Justala Simpson, an incoming student at the Candler School of Theology, this moment has only solidified her decision to pursue a divinity degree.

Her senior capstone project at Huntingdon College in Montgomery, Ala., was about the development of black theology juxtaposed with the exodus narrative. Watching social and economic disparities play out during the pandemic has only propelled her to study peace building, religion, and justice at Candler.

And while the potential of starting her seminary experience online “rattles her cage a little bit,” she said she is ready for whatever comes, especially for the future of the church.

Recently, she had to write a prophetic oracle in the form of either Isaiah or Micah for one of her classes at Huntington. She chose Isaiah. One of the lines from her oracle:

We filled our homes with toilet paper, while our mothers, fathers, and children are still in the streets crying.

"We think that because the church doors are open, that we've done our jobs," she said. But the pandemic has revealed that we have not truly extended ourselves to care for the widow, the orphan, and the poor.

Change is needed, she said. This moment could shake people of faith from their normal routines and inspire them to branch out beyond the four walls built around the church. It's an opportunity, she said, for "real ministry."

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!