Rose Marie Berger is a Catholic peace activist and poet. She has been on Sojourners staff since 1986, and worked for social justice movements for 40 years. Rose has rooted herself with Sojourners magazine and ministry. She has written hundreds of articles for Sojourners and other publications and is a sought after preacher and public speaker. After living in Washington, D.C., for 35 years, she moved to Oak View, Calif., in 2022.

Rose’s work in Christian nonviolence has taken her to conflict zones around the world. She is active in the Catholic Nonviolence Initiative, a project of Pax Christi International, and served as co-editor for Advancing Nonviolence and Just Peace in the Church and the World, the fruit of a multiyear, global, participatory process to deepen Catholic understanding of and commitment to Gospel nonviolence. Her poetry has appeared in the books Watershed Discipleship: Reinhabiting a Bioregional Faith and Practice and Buffalo Shout, Salmon Cry: Conversations on Creation, Land Justice, and Life Together. She is author of Bending the Arch: Poems (2019), Drawn By God: A History of the Society of Catholic Medical Missionaries from 1967 to 1991 (with Janet Gottschalk, 2012), and Who Killed Donte Manning? The Story of an American Neighborhood. She has also been a religion reviewer for Publishers Weekly and a Huffington Post commentator. Her work has appeared in National Catholic Reporter, Publishers Weekly, Religion News Service, Radical Grace-Oneing, The Merton Seasonal, U.S. Catholic, and elsewhere. She serves on the board of The International Thomas Merton Society.

With Sojourners, Rose has worked as an organizer on peace and environmental issues, internship program director, liturgist, community pastor, poetry editor, and, currently, as a senior editor of Sojourners magazine, where she writes a regular column on spirituality and justice. She is responsible for the Living the Word biblical reflections on the Revised Common Lectionary, poetry, Bible studies, and interviews – and oversees the production of study guides and the online Bible study Preaching the Word.

Rose has a veteran history in social justice activism, including: leading the first international, inter-religious peace witness into Kyiv, Ukraine, following the outbreak of war in 2022, organizing inter-religious witness against the Keystone XL pipeline; educating and training groups in nonviolence; leading retreats in spirituality and justice; writing on topics as diverse as the “Spiritual Vision of Van Gogh, O'Keeffe, and Warhol,” the war in the Balkans, interviews with Black activists Vincent Harding and Yvonne Delk, the Love Canal's Lois Gibbs, and Mexican archbishop Ruiz, cultural commentary on the Catholic church and the peace movement, reviews of movies, books, and music.

Rose Berger has taught writing and poetry workshops for children and adults. She’s completed her MFA in poetry through the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast program. Her poetry has been published in Sojourners, The Other Side, Radix and D.C. Poets Against the War.

Rose grew up in the Central Valley of California, located in the rich flood plains of the Sacramento and American rivers. Raised in radical Catholic communities heavily influenced by Franciscans and the Catholic Worker movement, she served for nine years on the pastoral team for Sojourners Community Church; five as its co-pastor. She directed Sojourners internship program from 1990-1999. She is currently a senior editor and poetry editor for Sojourners magazine. She has traveled throughout the United States, and also in Ukraine, Israel/Palestine, Costa Rica, the Netherlands, Northern Ireland, Bosnia, Kosova, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, and El Salvador visiting primarily with faith communities working for peace in situations of conflict.

Rose was born when atmospheric CO2 was at 319.08 ppm and now lives with her wife Heidi Thompson in Oak View, Calif., in the Ventura River watershed on traditional Chumash lands. Learn more at rosemarieberger.com.

Rose’s articles include:

- Pursuing the Secret of Joy: What is joy when it's not promiscuously tied to happiness, Hallmark, or hedonism?

- Why Our Faith Delegation went to Ukraine?: Our public message was simple: “We have come to Kyiv in solidarity to pray for a just peace.”

- Nonviolence in Najaf?: Will we recognize an Islamic peace movement when we see it?

- Of Love's Risen Body: The poetry of Denise Levertov, 1923-1997

- Glimpses of God Outside the Temple: The spiritual vision of Vincent Van Gogh, Georgia O'Keefe, and Andy Warhol.

- Damnation Will Not Be Televised: Almost everything I know about hell I learned from watching Buffy the Vampire Slayer

Speaking Topics

- Christian nonviolence, peace, war

- Catholic Nonviolence Initiative

- Climate change, creation care, watershed discipleship

- Bible study, liturgical year

- Poetry

- Spirituality and social justice

- Any topic covered in Sojourners magazine

- Catholicism

Speaking Format

- Preference for virtual events, but willing to discuss in-person events on case-by-case basis

Posts By This Author

Spiritual Reflections on My Paycheck

MONEY IS TO Americans what sex was to Victorian England. We’ll read about others’ exploits, but rarely reveal our own.

In the mid-1980s, I joined the Sojourners base Christian community. I was in my 20s with little disposable cash and a modest college loan. My theological attitude was “love of money is the root of all evil” (1 Timothy 6:10)—even thinking about money risked sliding into America’s amorous relationship with capital.

Madame Jazz vs. Madame Guillotine

IRISH POET Patrick Kavanagh famously said, “Any poet worth his salt is a theologian.”

In The Five Quintets, a poetic tour de force by Micheal O’Siadhail, Kavanagh’s quip is flavorfully borne out. Quintets offers a sustained reflection on Western modernity (and its yet unnamed aftermath) in the vein of The Divine Comedy, Dante’s sustained reflection on medieval Europe (and its aftermath, the Renaissance).

O’Siadhail (pronounced O’Sheel) inspects 400 years of Anglo-Atlantic culture—artistic creativity, economics, politics, science, and “the search for meaning”—with the skillful hand of a citizen-poet, refracted through an Irish Catholic soul. Dublin born and educated, now poet in residence at Union Theological Seminary in New York, O’Siadhail embodies the vatic tradition of the Hibernian Gael—poet, prophet, priest, and, at times, jester.

His blind guide for the modern era is Madame Jazz—who encompasses klezmer from the Jewish shtetls and céilí music from famine Ireland as well. Jazz is the consummation of all that is truly human, the best of our polyphonic harmonies, a wild, joyful freedom born of shared suffering. Her chilling counterpoint, who ends the age of monarchs, is Madame Guillotine, whose shadow reaches forward into our War on Terror.

Power Dynamics and Sexual Ethics

UNITED METHODIST BISHOP Cynthia Moore-Koikoi has fond memories of growing up in the church. It helped form and develop her as a leader, she said. But her involvement with church administration and leadership came with a price, as she described in a panel at the Religion News Association conference in 2018. As a youth delegate to her annual convention, Moore-Koikoi recalled that whenever she walked by a certain group of clergy, “they were going to make comments about my physical appearance ... I learned how to turn my face quickly when that ‘holy kiss’ was given so that it would land on my cheek not on my lips. It was like I was walking a gauntlet at times.”

In 2016, Moore-Koikoi was consecrated as a bishop and called to serve United Methodists in western Pennsylvania. Certainly, she thought, serving in such a high church position and marriage would protect her from sexual comments and predation. But, says Moore-Koikoi, “no level of power or authority in the church can insulate persons from sexual harassment.” Sojourners’ senior associate editor Rose Marie Berger interviewed Moore-Koikoi by phone in December 2018.

Sojourners: In 2016 you were elected bishop. Have you experienced any sexualized pressure, harassment, or assault since your ordination as a bishop?

Bishop Cynthia Moore-Koikoi: Yes. There was an incident that happened not long after I was ordained a bishop that I characterize as sexual harassment. Unfortunately, it happened at one of the earliest meetings that I went to as a bishop with the Council of Bishops. An individual there made some inappropriate comments about me, about my physical appearance and about his desires. It was a very uncomfortable situation, [my] being a new bishop, not knowing how bishops conduct themselves at those kinds of things.

‘Because of my chains...’

WHAT DO YOU see in the photo at right? Name all the objects. Spend a moment.

Hillside erosion. A semi-trailer truck with sleeper unit and maple leaf logo. Chain-link fence. Two people. U-locks at necks. Banner. Ecclesiastical stole. Heavy-grade straight chain. Clerical collar. Tree trunk. Small orange ribbon.

What is the subject of the photo? What does the camera leave out?

Photographer Murray Bush took this photo last year on May 25 on Burnaby Mountain in British Columbia. The truck is for horizontal drilling and belongs to the firm Kinder Morgan, one of the largest energy infrastructure companies in North America. The company specializes in pipelines and petroleum terminals and is the first pipeline operator to purchase a fleet of oil tankers. The fence marks a boundary—and contested space.

The two people, Laurel Dykstra and Lini Hutchings, are members of Salal + Cedar, a Christian community in Coast Salish territory. The lock-on hardware around them—the U-locks and chain—is to delay removal by the 17 Royal Canadian Mounted Police who showed up. In 2015, the Anglican Diocese of New Westminster appointed Dykstra as a sort of “priest to the Fraser River watershed.”

No More Cover-Ups

I AM ROMAN CATHOLIC, and I want to apologize. Apparently, a portion of my church not only believes in but still practices child sacrifice.

The Pennsylvania grand jury report was clear. It opened: “We, the members of this grand jury, need you to hear this. We know some of you have heard some of it before. There have been other reports about child sex abuse within the Catholic Church. But never on this scale. For many of us, those earlier stories happened someplace else, someplace away. Now we know the truth: It happened everywhere.”

For more than 30 years, investigations around the world have revealed similar patterns in Catholic institutions. Priests, bishops, cardinals, and even popes have decided that the Roman Catholic Church is too big to fail—that perpetrators of child abuse should be “bailed out” and victims given cash and gag orders to protect the idol of a religious corporation.

Since medieval times the Catholic Church has operated as an artificial legal persona to put property in perpetual collective ownership: the first legal corporation. If diocesan priests are considered “shareholders,” then the Catholic Corporation has willingly sacrificed children in the name of shareholder protection, betraying any legitimate “pro-life” ethic it might publicly promote. In the Bible this profanity is called the “worship of Molech,” an ancient god of Israel’s enemies: Molech’s outstretched arms of bronze were held in fire until red-hot, then living children were placed in his hands.

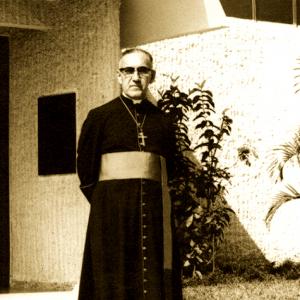

San Romero de la America

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in a 2005 issue of Sojourners magazine.

"El Papa Juan Pablo Segundo Murió" read the banner shown on the TV set in the El Salvador bar I was sitting in April 2, 2005. The pope's death had been rumored all week. One taxi driver told me the pope was dead, though the next one informed me he was not.

In Suicide, Who Sinned?

SUICIDE IS A SIN. As a Catholic, that’s what I was taught. Life is a gift from God; only God can take it away. Suicide chooses despair over God.

But I’ve never understood suicide to be an individual sin. It’s a communal one—based in a profound failure of love.

This past spring, two young men committed suicide while in the custody of the Department of Homeland Security. Beyond individual and communal sin is structural sin—when lovelessness is made into policy and enacted with cruelty. Note all the places where love failed.

In May, Marco Antonio Muñoz, a 39-year-old Honduran refugee, died in a south Texas jail cell of apparent suicide a few days after being forcibly separated from his wife and 3-year-old son at the U.S. border. And I mean “forcibly.”

When Border Patrol agents told Muñoz that the family would be separated, he “lost it,” according to The Washington Post. “‘The guy lost his s—,’ an agent said. ‘They had to use physical force to take the child out of his hands.’”

Muñoz was transferred to a county jail and placed in a padded isolation cell. Guards checked on him every 30 minutes. Reportedly, every time the guards passed during the night, they noted him praying in the corner of his cell. By morning, Marco Antonio Muñoz was dead.

3 Things U.S. Catholic Bishops Can Do About Family Separation and Incarceration at the Border

In this violent crisis, not significantly mitigated by President Trump’s recent executive order,every Catholic bishop becomes a “border bishop.” The tools of active nonviolence offer a way forward. In the first World Day of Peace message, Blessed Pope Paul VI said, “Peace is the only true direction of human progress — and not the tensions caused by ambitious nationalisms, nor conquests by violence, nor repressions which serve as mainstay for a false civil order.” He warned of “the danger of believing that international controversies cannot be resolved by the ways of reason, that is, by negotiations founded on law, justice, and equity, but only by means of deterrent and murderous forces.”

Charlottesville, the Summer After

Kim Kelley-Wagner Shrouded statue of Robert E. Lee in a Charlottesville park.

THERE IS NOTHING new under the sun, as the author of Ecclesiastes reminds us. In this, theologian Elsa Tamez said, we can “find solidarity in our discontent.”

I visited Charlottesville in May, nearly a year after the “summer of hate.” I heard from young Christians who had been on the frontlines at Robert E. Lee Park (now called Emancipation Park). I stood in the presence of their discontent, listening and witnessing to the ongoing, traumatizing effects of last summer’s “fascist lollapalooza,” as one University of Virginia professor put it.

Still reckoning with the memory of Aug. 12, one leader in his 20s shared how he had tried to be a nonviolent defender amid multiple “armed actors,” including the Ku Klux Klan, neo-Nazis, anti-fascists, and police. By the end of that day, two state troopers were dead, one woman was murdered, dozens were injured, and the whole community was emotionally, spiritually wounded.

Game Changer?

“JUST WAR IS KILLING US! There is no just war.”

That proclamation by a Catholic sister from Iraq, and others like it, resounded at a Vatican gathering this spring and fell on surprisingly receptive ears.

Sister Nazik Matty, an Iraqi Dominican, joined others from around the world in Rome in April to wrestle with how the Catholic Church could “recommit to the centrality of gospel nonviolence.” She has watched members of her religious community die for lack of medical care during war.

“Which of the wars we have been in is a just war?” asked Sister Matty, who was driven from her home in Mosul by ISIS, also known by the Arabic acronym Daesh. “In my country, there was no just war. War is the mother of ignorance, isolation, and poverty. Please tell the world there is no such thing as a just war. I say this as a daughter of war.”

The Rome gathering on Nonviolence and Just Peace was unprecedented, bringing together members of the church hierarchy with social scientists, theologians, practitioners of nonviolence, diplomats, and unarmed civilian peacekeepers to discuss Catholic nonviolence and whether in the contemporary world armed force can ever be justified.

Of course, with such diverse participants, there was not a common mind on whether just war theory, a doctrine of military ethics used by Catholic theologians, has outlived its usefulness as church teaching.

Some of the academics and diplomats—particularly from the United States and Western Europe—maintained that just war criteria, when properly applied, are useful when working within halls of power, from the Pentagon to the United Nations, for restraining excessive use of military force by a state. One participant cautioned against “broad condemnations of just war tradition, if it means closing off dialogue with our allies.” Another questioned how diplomacy could continue without the just war framework as its common language.

But Catholics who came to Rome from conflict zones—Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Palestine, Colombia, Mexico, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi, and Uganda—brought a different perspective.

An Abundance of Cultural Differences

Awe Inspiring Images / Shutterstock.com

'WE CAN JOYFULLY anticipate an abundance of cultural differences and varied life experiences among the participants in the Rome Conference,” wrote Pope Francis in his welcome letter to the Nonviolence and Just Peace gathering in Rome, “and these will only enhance the exchanges and contribute to the renewal of the active witness of nonviolence as a ‘weapon’ to achieve peace.”

Nowhere were the “cultural differences” and “varied life experiences” more conspicuous than in the conversation about whether there is ever a Christian justification for armed force.

U.S. and Western European academics are thoroughly trained in the theory, theology, and application of just war theory. It’s taught in U.S. and European seminaries. It’s taught in all military academies. It provides a framework for international law.

In stark contrast, Catholics living in Iraq, Sudan, Uganda, Afghanistan, Syria, Congo, Sri Lanka, and other war-torn countries are not schooled in just war philosophy. It is not part of training for priests or academics or those in political life. When people from war-ravaged regions talk about “just war,” they speak from the experience of having been on the receiving end of “morally acceptable” drone strikes. They make a powerful argument for a paradigm shift away from just war thinking.

In regions of civil unrest, some said, where religious extremism is used as propaganda to advance partisan military and political objectives, even associating the language of “just war” with Catholicism can categorize Catholics as “combatants.”

In the case of Colombia’s brutal, 52-year-long civil war, Jesuit priest Francisco De Roux described how just war teaching misled Catholics into taking up arms. “In my Catholic country,” said De Roux, “our nuns and priests join the guerillas because of the just war paradigm. The Catholic paramilitaries pray to the Virgin before slaughtering people because of the just war paradigm.”

The Mosquito Manifesto

WHAT DO YOU do when the democratic process delivers the power of the presidency to an authoritarian leader with the strategic impulse control of a 2-year-old?

Here are a few responses I’ve observed.

OPTION 1: The Ostrich. Bury one’s head in the sand until the annoyances pass. The virulent rhetoric of Mr. Trump’s campaign, combined with his appointees and advisers, make this option available only to men of European decent. (White women may cover their heads, but shouldn’t bury them completely.)

OPTION 2: The Spaniel. Fluff up one’s coat and appear clean and eager on the doorstep of the new master. Hope for the best; hope for a bone. This option is supported by many who are well-meaning, are part of the political elite, or are dangerously naive.

OPTION 3: The Cockroach. When the light comes on, scatter into the street with a sign saying “Not My President.” Or simply hide in a dark corner hoping to pass the coming wrath undetected. This escape behavior is instinctual in creatures that are startled or undeveloped.

Since the wee hours of Nov. 9, I’ve exhibited most of these behaviors myself.

But as a Christian, I’m not allowed to live in illusions for long. In Paul’s “letter of tears,” written to the fledgling church at Corinth, he wrote, “We cannot do anything against the truth, but only for the truth” (2 Corinthians 13:8). Therefore, existing in a “post-truth” state is not an option.

Americans are deeply disillusioned about the state of our nation. The fundamental optimism of the “American dream” has not matched reality for at least three generations. American optimism has always been partly delusion, as evidenced by the experiences of those defined outside of it or on whose backs the “great good” was built.

An election, however, is supposed to be a tool for the nonviolent transfer and distribution of power, not a therapy session to deal with disillusionment.

When You See Something ... Act!

ROBERT HARVEY had a problem. The church he pastors was vandalized after the election: “Trump Nation. Whites only” was scrawled across its sign. His congregants, nearly 85 percent of whom are immigrants from West Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean, were shaken.

The Southern Poverty Law Center reported 1,094 bias-related incidents across the country in the month after the election. The greatest number of these types of events are against women in public spaces who are also immigrants, Muslim, or African American. These are assumed to be a “small fraction of hate-related incidents,” as the Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates that two-thirds of hate crimes go unreported.

Harvey, rector of Episcopal Church of Our Saviour in Silver Spring, Md., decided to take action. First, he reached out to the local community and other religious congregations. Second, he signed up for a nonviolence and “active bystander intervention” training.

To understand how to be an “active bystander,” one must first understand the “passive bystander” effect. Research shows that when someone needs help and they are in a crowd, bystanders are less likely to act. The more bystanders there are to an event, the more each one thinks someone else will help.

The Beatitudes and Executive Order 13767

OUTSIDE, A HELICOPTER circles this D.C. neighborhood, a dog barks anxiously in the alley. Inside, a woman sits in a straight-backed chair reading the Beatitudes. She adjusts her glasses. “Bienaventurados los que lloran, porque ellos recibirán consolación.” Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted. “It’s a beautiful prayer,” she says.

My neighbor Lola cleans office buildings during the week, takes English classes on Saturdays, goes to Mass on Sundays. Her husband operates a jackhammer for a construction crew. On the “Day Without Immigrants,” Lola’s boss said because it wasn’t organized by the union, workers should not stay home. So she went to work. Her husband stayed home. “We have to stand together,” he said.

Lola and her husband sometimes share their one-bedroom apartment with a man who was their neighbor in El Salvador. He works days, nights, weekends. He sleeps on a mattress in their main room for a few hours in the afternoon. Lola leaves pupusas for him, wrapped and warm. Sometimes he drinks too much, turns up the radio, dances. They quiet him so he doesn’t disturb the neighbors. He feels safe there.

Total Eclipse (of the Soul)

THIS WON'T HAPPEN again until 2045. On Aug. 21, the thumb of God (with a little help from the moon) will smudge out the sun. A total solar eclipse will mark the brow of the United States with a Stygian darkness so deep that stars will unmask in midday. From Lincoln City, Ore., to Charleston, S.C., “flyover” America will go dark.

In Hebrew tradition, the darkening of the sun or reddening of the moon are markers of cataclysmic political events with spiritual consequences. In Greek, eclipse means “abandonment,” in Hebrew “defect.” God’s light is in a state of hiddenness.

Piracy and Puritanism at Wells Fargo

Northfoto / Shutterstock.com

I OPENED MY first savings account at Wells Fargo in Sacramento, Calif., when I was 8 years old. I remember the bronze stagecoach penny bank they gave me to help me practice saving. When I moved to Washington, D.C., I put my money into a D.C.-based bank, soon bought out by Wells Fargo. But it wasn’t the same Wells Fargo I’d grown up with.

In 2012, the Justice Department found Wells Fargo guilty of discriminating against both African-American and Latino borrowers during the subprime mortgage heist. It’s one of the top two banks invested in the Corrections Corporation of America, which is one of the largest for-profit prison companies in the U.S. In 2015, Wells Fargo was the world’s largest bank.

This fall, Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf, who abruptly resigned in October, was called before a congressional investigative committee to answer accusations that thousands of Wells Fargo employees secretly opened 2 million fraudulent accounts without customers’ permission or knowledge, and were incentivized by the company to do so. Employees opened false banking and credit card accounts, transferred funds, and created phony access codes and email addresses. “The frauds violate federal and state statutes against bank fraud and identity theft,” William K. Black Jr., white-collar criminologist and cofounder of Bank Whistleblowers United, told Sojourners. Customers incurred charges and fines; in some cases, their credit ratings were damaged.

CEO Stumpf accepted “full responsibility for all unethical sales practices in our retail banking business.” (John Steinbeck once called this kind of thing a successful combination of “piracy and puritanism.”)

Wells Fargo claims that it has fired 5,300 people since 2011 related to these practices, but details are vague; the fraud investigators were hired by Wells Fargo. We don’t know how many were fired because they couldn’t fulfill the extortionate sales quotas.

Bosnian Butcher Radovan Karadžić Says Genocide Conviction Based on Jokes

"America, keep your peace. You don't know how precious it is and how terrible is war."

Bond Denied for 7 Catholic Protesters Who Prayed on Nuclear Submarine Base in Georgia

Just steps away from a decommissioned submarine buried in the ground near the main gate at the Kings Bay Naval Submarine Base in Georgia, anti-nuclear peace activists held a vigil Saturday morning to protest the U.S. nuclear arsenal and to show support for seven Catholic peace activists arrested early Thursday morning for unauthorized entry onto the base.

Life Inside a Tomb

IT IS HARD to tell time from inside a tomb. We cannot know how many minutes or hours Jesus’ resurrection took. Traditionally, he was in the tomb for three days. But how long does it really take for someone to rise—or be raised—from the dead?

Some resurrections start at a mundane moment. Dorothy Day, for example, was sitting at the kitchen table in a crowded apartment in New York’s East Village (writing a never-to-be published novel) when the French Catholic theologian Peter Maurin knocked on the door. “It was a long time before I really knew what Peter was talking about that first day,” wrote Day, who went on to found the Catholic Worker movement with Maurin. “But he did make three points I thought I understood: founding a newspaper for clarification of thought, starting houses of hospitality, and organizing farming communes. I did not really think then of the latter two as having anything to do with me, but I did know about newspapers.”

Some resurrections come through brutal suffering. Twenty-four-year-old Recy Taylor was left for dead in 1944 on a dark road near Abbeville, Ala., by the six white men who kidnapped and raped her as she walked home from a prayer meeting at Rock Hill Holiness Church. “A few days later, a telephone rang at the NAACP branch office in Montgomery,” wrote historian Danielle L. McGuire in At the Dark End of the Street. The president of the local branch promised to send his “best investigator” to speak with Recy Taylor. The investigator’s name was Rosa Parks. As part of Park’s organizing work on Taylor’s case, she formed what would become the Montgomery Improvement Association, the leaders responsible for instigating the bus boycott a decade later, an opening salvo of the civil rights movement.

An Outline for a Service Acknowledging War Crimes

“Has the United States ever apologized?

Or are we too big to apologize?”

—Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson

The Chaplains Handbook has no confiteor or rite,

neither Book of Common Prayer nor missalette,

for scrutinies that beg forgiveness from the torn

and desecrated dead. We come contrite

for reports of helicopter gunships,

bodies observed in a ditch, the undress

of a girl who covered only her eyes:

Noncombatant gang rape, with bayonet.