While many have pointed out important comparisons between COVID-19 and the Spanish Flu of 1918, the economic “Panic of 1893” and our current moment also share much in common. Both are incredible moments of contingency, when the shortcomings of economic and social structures are laid bare and people experience firsthand their failures.

In 1894, the journalist William T. Snead announced that “Chicago, like other cities, is possessed by a host of unclean spirits, whose name is Legion, for they are many.” In If Christ Came to Chicago, Snead wrote about his belief that the entirety of the industrialized world had become overrun by demonic forces.

Despite the suggested premillennialism of the title, Christ’s second coming was not imminent, but the world was at a crossroads. The demonic forces at work were not spiritual. They were material. Plutocracy, compound interest, economic inequality, and religious discrimination had possessed the nation. But, there would be no rapture to rescue it. Only structural reform could redeem it.

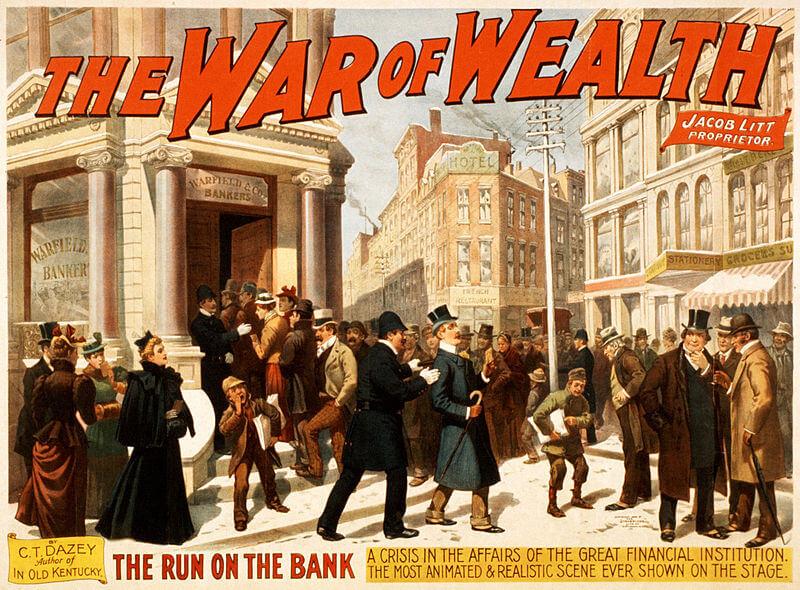

The bleak and unequal society that Snead wrote about in 1894 was the product of industrial and economic transformations that had been taking place over the course of the 19th century, and had quickened in the 1880s and 1890s. The Panic of 1893, the first major economic recession of the second industrial revolution, made it much worse, revealing how intertwined and unfair the new global economy had become. It began when the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad declared bankruptcy. Subsequent bank defaults caused a banking crisis, thousands were thrown out of work, the price of agricultural products collapsed, and farmers across the nation lost their farms. The Panic undermined many of the central industries of the American economy and revealed its problems.

800px-war_of_wealth_bank_run_poster_1.jpg

After 1893, many people believed that capitalism had failed. Some wanted to go back to the pre-industrial economy of the early 19th century — they wanted to go back to "normal." Others wanted to move past capitalism to find a fairer system. But both agreed that the current system of American capitalism had failed profoundly, and it was new enough that neither believed they were bound to it. It wasn’t yet an inevitability.

The Panic of 1893 inspired labor and politicians. In 1894, in response to lay-offs and cut wages, workers at the Pullman factory went on strike. In solidarity, workers across the nation refused to work on any trains carrying Pullman cars. Train traffic in the nation came to a standstill. The gears of industry would not turn without workers. In 1896, talking about monetary policy, William Jennings Bryan pleaded that the nation should not be allowed to “press down upon labor [a] crown of thorns,” and that the nation should not crucify its people “on a cross of gold.”

But the strikes were defeated. And the elections were lost. The new world was not to come. Our COVID-19 pandemic is another contingent moment. The failures of American capitalism are once again on display.

Workers cannot stay at home because they don’t have paid sick leave. Meat plant workers, many of them Latino immigrants, are forced to return to work in plants that were already unsafe. Now in addition to loss of limbs, because of COVID-19, they could lose their lives. Agricultural workers, who have faced low wages and poor working conditions for decades, are also facing the coronavirus. Out of school and without internet, many young Latinos have instead gone to work in the fields with their families.

The lack of health care has made a health crisis even harder to manage. Public health officials have known for decades that health is not just a matter of personal choice, but the product of a combination of social determinants. Where people live, work, eat, and sleep are factors in health outcomes. For these reasons, poorer communities have poorer health. That’s why poorer communities of color have died at higher rates from COVID-19.

The continued dismantling of the social safety net since the 1970s has made the sharp economic recession worse. The Trump administration’s new work requirements will deny even more families necessary food. Over 33 million have lost their jobs during the pandemic, a number that is most likely an undercount. Most applicants ran into problems applying and state unemployment offices were overrun. Unfortunately, most state unemployment programs had been underfunded and understaffed for years. In order to discourage would-be applicants, many were designed to be inefficient, running on outdated computer code.

The gig economy was supposed to disrupt the old models of employment. What the pandemic has made clear is that the supposed disruption was only a redefinition of “employee” to “subcontractor.” While the work changed very little, the legal reassignment limited the responsibilities and liabilities of employers. Workers had very little protections and high levels of insecurity.

But, there is a glimmer of hope.

The pandemic has made clear how essential workers in the food and service industries are. Meat plant workers, produce pickers, grocery and restaurant workers keep the nation alive. With that realization, many should understand that their labor is worth $15 an hour, at minimum. Warehouse workers too have shown how central they are to our lives and economy. With renewed confidence, workers at Amazon, Target, Walmart, and Whole Foods even staged a nationwide general strike on May 1.

Social distancing policies have changed work across the nation, in some cases for the better. Prior to the outbreak, only about 4 percent of people worked from home. Now, 34 percent of Americans are working from home. With fewer people driving to the office, pollution is declining. With fewer people commuting, more people are spending time outside, walking, running, and riding bikes. Some cities have even closed roads to traffic so that people can walk in the streets.

These changes don’t have to be temporary.

We can rethink the office building, which has shown that it is much more like the 19th century factory, a tool of employer control and surveillance. We can rethink the designs of our cities, prioritizing green space and leisure over cars and commuting. This reimagining will not just make us safer in the case of future pandemics, but make us healthier and happier in the long run.

We can and should rethink work and labor. It is time to reconsider the 40 hour work week, employer-based health insurance, and retirement accounts. Two once-in-a-lifetime recessions and a global pandemic have made most of those systems seem untenable. Our health and retirement should not be dependent on corporations that will sacrifice workers for shareholders. With millions out of work, waiters and primary care physicians alike, we should discard our notions of the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor. After this, nobody should be comfortable with the categories that Paul Ryan once described as the “makers and takers.”

It seems like a different world is possible, but we must make the necessary changes. In the 1890s, Snead wrote about the dangerous spirits of American profligacy. If Christ had come to Chicago then, he would have warned of the greed in the economic system. So, while the specter of the Spanish Flu may scare us, it is the demons of 1893 that should haunt us.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!