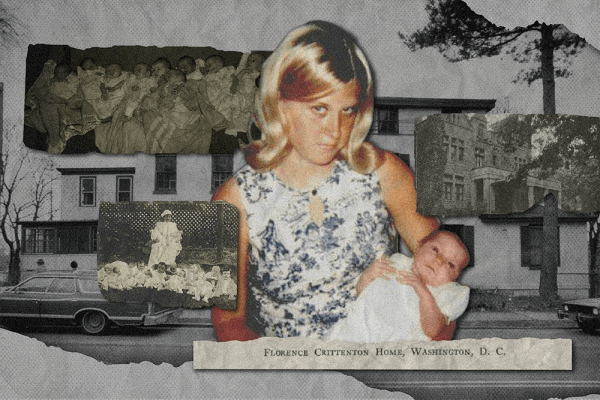

When Francine Gurtler gave birth at age 15, she felt like she lost her voice. Gurtler lived at an Episcopal home for unwed mothers and said the workers of the home coerced her into placing her baby for adoption.

“They literally took him from my arms,” she said. The adoption record notes she was “tearful,” but Gurtler said, “I was sobbing, hysterically, uncontrollably, on the ground begging the social worker to let me keep my baby.”

Now, she is lobbying the Episcopal Church to make to make an apology for forcing her and other women and girls to relinquish their children for adoption while receiving services in the church’s maternity homes.

Raised an Episcopalian, Gurtler entered St. Faith’s Home for Unwed Mothers, operated within the New York diocese of the Episcopal Church, in 1971. The adoption records included: “The birth mother told this social worker that she knew she had to give up her son as there was no other way, but she loved him and wished she could have kept him.” Gurtler told Sojourners: “There was no other way because I was not given a choice.”

In 2017, she was reunited with her son through a DNA test. The reunion was drawn out over a few years’ worth of phone calls and trips. It was emotionally draining, particularly as members of her reunited family still thought of Gurtler as “giving up” her son. After a cross-country trip to visit him, “I had a full-blown panic attack and went home,” she said. “That put me on the journey to finding the truth.”

For a long time, she thought she was the only one who felt her child was stolen from her and given to another family. During late night internet surfing, she discovered another mother forced to surrender her baby: Karen Wilson-Buterbaugh, who wrote The Baby Scoop Era documenting forced adoptions between 1945 and 1972.

In 2021, Gurtler found the Catholic Mothers for Truth & Transparency — a group formed to speak against Catholic institutions that forced adoptions. The mothers successfully advocated for a 2021 Connecticut law to allow adoptees to access their original birth certificates.

“It is widely recognized we have endured a trauma by losing our children to adoption, but the overwhelming majority of us are actively trying to heal in the face of this trauma,” the group wrote in an op-ed in The Connecticut Mirror. “We do so by regaining our voices and our power that was lost at relinquishment.”

Energized by that win, the mothers turned next to asking for an apology from the Catholic Church. While other institutions, including churches, have apologized for forced adoptions in other countries, no church institutions in the U.S. are known to have apologized. The Episcopal Church declined to comment until after its executive council meets in late October 2023.

Gurtler, who is still an involved member in the Episcopal Church, wondered if she could successfully get the denomination to apologize for their role in forced adoptions. She sent emails to every bishop and any clergy member she thought might help sponsor a resolution. Eventually, she met Mark Diebel, a retired priest and adoptee. Together, they wrote a paper for a resolution at the 2022 Episcopal general convention, including the research of Wilson-Buterbaugh.

The church passed the resolution acknowledging its role in running maternity homes, where forced adoption took place. According to Gurtler’s research, the Episcopal Church ran at least seven maternity homes across the country, as well as having a role in the network of other homes. While it’s unknown if all maternity homes coerced mothers into giving up their children, historian Rickie Solinger described in her book Wake Up Little Susie how abusive adoption practices became common all over the country from the end of World War II to 1973 when Roe v. Wade passed.

The Baby Scoop Era

Wilson-Buterbaugh estimates that 1.5 million mothers were forced to relinquish their infants to adoption during this time. She refers to it as the “Baby Scoop Era.” Unmarried mothers in the U.S. and other anglophone countries faced coercion by social workers and societal attitudes toward their “sin.” Young, single, mostly white women, who became pregnant, were commonly sent to live at maternity homes, often against their will. Most maternity homes were operated by religious institutions.

Wilson-Buterbaugh said she “had no control in 1966 when [her] baby was taken” by a Catholic social worker at the Florence Crittenton Home in Washington, D.C.

According to several reports found by Wilson-Buterbaugh, there were between 150 and 190 maternity homes in the U.S. in the 1960s. Three-quarters of the homes were affiliated with either the Florence Crittenton League (a charity that helped “reform” unwed mothers, also known as National Florence Crittenton Mission), the Salvation Army, or various Catholic charities. The others were run by other religious groups or independent agencies, including by Episcopal organizations.

“When you hear, ‘Well, oh well it was the times, that’s why they did it.’ Bull---- on that,” said Gurtler.

According to Wilson-Buterbaugh’s book, mothers were not generally pressured to relinquish their children in the early decades of the 20th century. She describes the “Baby Scoop Era” as a regression on a timeline of women’s rights.

National Florence Crittenton Mission was established in 1883 by Charles Crittenton and Dr. Kate Waller Barrett, who were both Episcopalians. The homes would provide mothers shelter, medical care, discipleship, and job training. Mothering was considered a path to reform. Barrett wrote in 1903, “During all the years that our home has been opened we have never consented in a single case to the child being given away.” Over the years, the Crittenton homes expanded across the country and world to include over 70 independently operated homes.

A 1923 St. Faith’s report released from the diocese of New York doesn’t mention any adoptions among the 16 babies born that year. Instead, it notes the number of girls confirmed and babies baptized.

But in the decade leading up to WWII, historian Regina Kunzel found that social workers shifted to thinking of unwed mothers as “deviant” or even psychotic and unfit to parent. They increasingly began practicing relinquishment and adoption, believing it to be in the best interest of the child. In some maternity homes, mothers were not granted entrance unless they agreed to relinquish their child. Once there, mothers were isolated from society, their families, often the father of their children, then, ultimately, their child.

In the decades after World War II, infertile, white married couples, often wealthy, began turning to social workers to form families, creating a demand for adoptions. According to sociologist Gretchen Sisson, researchers agree that about 20 percent of babies born to white unwed mothers were relinquished during this era. By 1966, most mothers who stayed at St. Faith’s surrendered their children for adoption according to a document from the home’s director at the time.

Jeannette Pai-Espinosa, the current president of Justice + Joy (formerly the National Florence Crittenton Mission), said that people felt that white women “had more possibility or chances of reaching their hopes and dreams, and there were so many opportunities that they were going to miss if they had this baby,” she said. “That wasn’t the case for marginalized women of color.”

These racist expectations colored views on motherhood and adoption. Most people of color born during their mothers’ stay at Crittenton homes were still raised by their mother. As Sisson explained: In the Baby Scoop Era, white women faced shame, which was redeemable through adoption, while Black women faced blame, which resulted in discriminatory policies and attitudes toward Black families and children.

St. Faith’s closed in the mid-1970s, becoming a children’s home. Today, 25 Justice + Joy agencies still provide services to young women, but the priority is to enable mothers to remain with their children — a pendulum swing that Pai-Espinosa regards as true to the original mission. Though times have changed, she said “young motherhood is still influenced by the same complex mix of factors: race, gender, and class.”

An Episcopal apology?

If an apology is formalized, the Episcopal Church would be the first organization in the U.S. to facilitate an apology process for mothers and their children who were adopted. Two Canadian religious institutions formally apologized: the United Church of Canada in November 2020 and the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Vancouver in May 2022.

The United Church of Canada ran five maternity homes across Canada. “Women told us that they felt, pressured, coerced, or forced to give up their babies and the church recognizes it participated in the culture of shame that surrounded unmarried mothers at that time,” said Rev. Daniel Hayward, chairperson of the committee that recommended the apology.

To make reparations, the Vancouver archdiocese initiated trainings for Catholic counselors, social workers, and psychologists; ran articles in its regional newspaper; created a webpage of resources for adoptees and families of origin; and opened a hotline for those affected by adoption. Archbishop J. Michael Miller also gave a Mother’s Day blessing for mothers who were coerced to place their children for adoption.

Although the Episcopal Church no longer operates maternity homes, Gurtler and her counterparts worry that local dioceses and parishes continue to encourage the separation of mothers and infants via support of social and adoption agencies that pressure mothers to relinquish their infants.

Overall, she wants the church to stop promoting the narrative of adoption as “the most wonderful thing,” and instead favor natural family preservation.

She wants the church to support mental health services for women who relinquished their kids at church-operated maternity homes like St. Faith’s. She also wants the church to assist families in finding each other again; birth records are not accessible even to adoptees in every state, and adoption records themselves can be elusive.

For the Episcopal Church’s resolution, Pai-Espinosa wrote a letter expressing regret over the actions of Crittenton in coercing mothers into placing their children for adoption. “Not a month goes by that we don’t hear from someone searching for a family member and we are acutely aware of the pain and damage done by the past practices,” she wrote. She encouraged the church not to react defensively but to compassionately consider the consequences of the actions taken during this era.

Gurtler, now a speech pathologist, says joining other women in calling on religious institutions to apologize for forced adoption is finally helping her use her voice again. For herself, she simply wants the truth to be acknowledged.

“I just want someone to say to my son and my grandchildren: ‘We stole him from her,’” she said.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!