Illustrations by Brianna Robinson

‘If They Felt Safe ... They Would Not Leave'

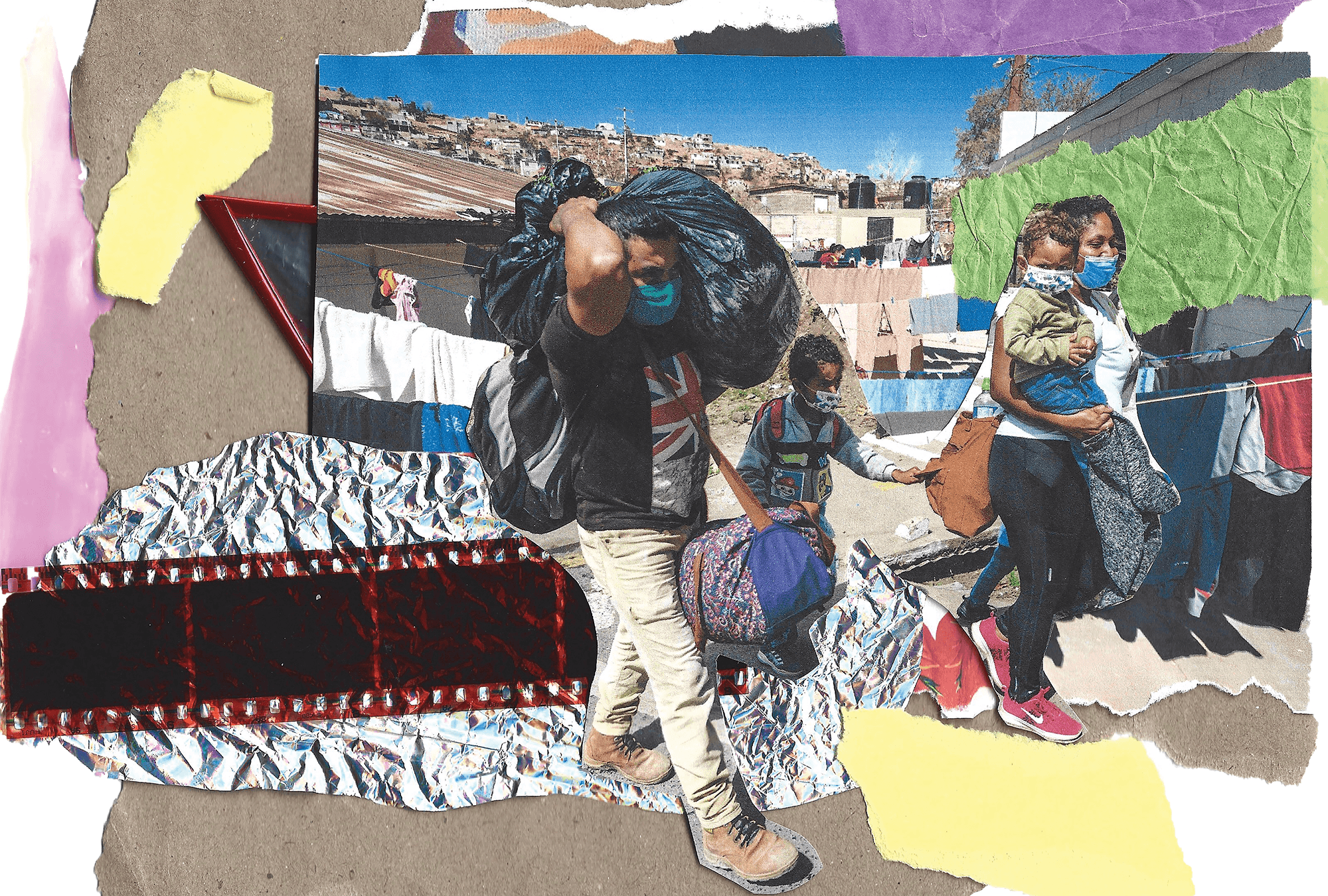

BININZIO NUÑEZ, STEPHANIE HERNANDEZ, and their children sit in the shade outside the Honduran customs office at a border crossing with Guatemala, recuperating and replenishing themselves with food and water supplied by the Guatemalan Red Cross. The family members, who came from a farming community in central Honduras, were deported from Guatemala on the morning of Jan. 19 this year. They had attempted the journey north by joining a large migrant caravan that departed San Pedro Sula, Honduras, in the early morning hours of Jan. 15.

Now, the family waits in the afternoon heat, one small group among several thousand people deported over the last few days, as other people expelled from Guatemala stream back into Honduras with their belongings in backpacks and trash bags.

Nuñez and Hernandez say they joined the caravan out of necessity. “There are no jobs,” Nuñez says. Back-to-back hurricanes, Eta and Iota, hit Central America in November 2020 and were especially punishing to Honduras. Nuñez says farm work has disappeared, and even the ever-growing clothing and assembly factories, or maquilas, aren’t hiring. The small pulpería (convenience shop) Hernandez operated was washed away by the storms.

They say they will make further attempts to reach the U.S., “probably California,” says Hernandez, holding her sleeping toddler. “We pray to God everything goes okay. There is nothing for us here.”

Sol Escobar, a bus driver hired by a Honduran emergency assistance agency to return those deported at the border to their homes, offers some context. He lived and worked in the U.S. for several years before returning to Honduras. “Mostly the young men, maybe some of the young women, will make it through,” Escobar says. “They will run past the police or into the forest or along the rivers to evade the checkpoints. But most of the families carrying their belongings or with children or older people will be stopped and sent back.”

Escobar’s assessment seems to bear out as most people seen returning to Honduras this day are families with children or senior adults. Still, clusters of young people also walk past.

Push and pull

THE CARAVAN HAD around 8,000 people, mostly Honduran with a small percentage of migrants from El Salvador and Nicaragua. Dramatic footage of clashes as migrants attempted to breach Guatemalan police lines at the border crossings and checkpoints bears witness to the challenges at the beginning of the journey. Not only do people need to find a way to travel the 2,000-plus miles to the U.S. border, they also face extortion by traffickers, hostility from local residents, and the perils of undocumented border crossings.

Arne Kristensen, a Danish consultant to international nongovernment organizations, has lived in Honduras since 2016 and worked with marginalized communities in the country for 20 years. He was in Chiquimula, Guatemala, assisting a news crew when violent confrontations between those migrating and police occurred on Jan. 17. Kristensen says half of those migrating who he spoke with in Guatemala pointed to loss of property during the November 2020 hurricanes as a “push factor” for their migration. The hurricanes are part of a pattern of extreme weather events attributed to climate change. Others listed job loss, lack of opportunity, violence or threats of violence from gangs, and political instability.

But Kristensen, who has a master’s degree in anti-corruption studies, believes the root of these problems are corrupt systems that make life unbearable for all but economic elites and those who participate in graft. “The cause of the cause [for these push factors] is corruption,” Kristensen says. “There is money, there are resources in the country. If people felt safe, if they felt they were taken care of and provided for, if they had opportunities for education and to educate their children, they would not leave. But in corrupt systems, these things do not appear attainable, and for many they are not.”

A January 2021 study titled “Hopelessness and Corruption” cited high numbers victimized by corruption—25 percent of Hondurans said they were victims of corruption in the previous year—and found that nearly 80 percent of people in the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala lack confidence in their government. Large numbers of people, the study reported, intend to migrate to another country—24 percent of Salvadorans, 33 percent of Hondurans, and 18 percent of Guatemalans.

Corruption in the region—which contributes to the sense of hopelessness that leads many to migrate—is deeply connected to U.S. intervention over the years. In Guatemala, for example, the CIA helped overthrow a democratically elected president in the 1950s and subsequently supported authoritarian leaders who murdered thousands of Guatemalans.

Kristensen also points to a significant “pull factor” for many Hondurans: The perception that wealth and freedom await those who complete the journey. More than 20 percent of the current Honduran GDP consists of foreign remittances. “Everyone knows someone who lives in the U.S.,” Kristensen says. “And if you’re a kid working in a mechanic shop for a lousy salary and your cousin is having success working in Houston and he wants to pay for you to come up, why don’t you do it?”

New faces of migration

ESTIMATES ARE ONLY now starting to emerge on the number of people who made it through Guatemala and into Mexico this year. Shelters in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas, where hopping a freight train known as “The Beast” is the fastest but most dangerous way north, are reporting record numbers of arrivals even as they’ve reduced bed space to enforce COVID-19 distancing protocols.

People who may not have undertaken the journey last year due to the pandemic are now feeling bolder. That, along with a perceived loosening of immigration policies under the Biden administration and the annual spring migration uptick, is seen as the impetus for the surge in early 2021 migrations.

In 2019, at least 500,000 people attempted the journey to the U.S. through Mexico. According to a July 2020 study by Jesuits in Honduras, coyotes—people paid to smuggle others across borders and into the U.S.—transported nearly 60 percent of those migrating north. Those migrating via caravans accounted for 15 percent of the total.

The percentage of people abandoning solo migration in favor of caravans has grown steadily in the past five years. Before that, few people migrated in large groups. “If we go together, we just might make it,” says Josué Rivera Rivera, a Honduran based in Mexico City, describing the sentiment he’s heard from many joining the caravans. Rivera is regional manager for the Protected Passage Program at ChildFund International, which is dedicated to safeguarding those migrating, especially children, adolescents, and their families, as they journey north.

“Children are the most vulnerable when it comes to migration,” Rivera says. “We really regret ... the [Trump administration] ‘Zero Tolerance’ policy and what it became: locking up children and systematically trying to make it as traumatizing as possible for the children, because they thought that would deter their families from migrating.”

Rivera points to other factors that have led to more families undertaking the journey. Prior to the U.S.-initiated war on drugs, the 9/11 attacks, and restrictions placed by the North American Free Trade Agreement, Rivera says, the border was more porous, and many people received worker visas to the U.S. annually to work in construction or agriculture. When the U.S.-Mexico border was militarized in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and migrant work visas became all but impossible to obtain, this seasonal flow of labor was halted, along with the flow of money that kept communities and families afloat in Mexico and Central America. “Going to the U.S. to work became a one-shot deal,” Rivera says. “The chances of coming back to your home country [and family] if you have gone to the U.S. are so much smaller. At the same time, other factors like political and social instability, murders, gangs, and extreme weather events became worse in Central America.”

Rivera has interviewed people on the migration path in Mexico; he estimates 80 percent reported experiencing a traumatizing event such as theft, gang violence, extortion, or police interference in their home country in the last six months. He added that they were headed for even more trauma en route, especially if apprehended along the way or at the U.S. border.

A human wall

IN FALL 2018, a 160-person caravan left San Pedro Sula, bound for the U.S. By the time it reached the Guatemalan border at El Florido, there were 3,000 people. According to U.N. estimates, the caravan temporarily swelled to 7,000 people as it approached the border with Mexico on Oct. 22. In response, then-President Donald Trump tweeted, “Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador were not able to do the job of stopping people from leaving their country and coming illegally to the U.S. We will now begin cutting off, or substantially reducing, the massive foreign aid routinely given to them.”

“Before Trump, nobody thought of caravans,” says Milton Funes, a consultant with Global Communities. Traveling with other people, Funes says, “There’s less risk of traffickers and extortion along the route. It also sends a message that there is a large presence of people suffering, looking for a better way of life, a dignified life.”

It’s unknown how many people in the 2018 caravan arrived at the U.S. border, given attrition through exhaustion and lack of funds, but on Nov. 23 the mayor of Tijuana, Juan Manuel Gastélum, declared a humanitarian crisis in his city as 5,000 travelers crammed into the city’s 3,000-person capacity soccer stadium in anticipation of seeking asylum. U.S. agencies were able to process fewer than 100 asylum applications per day, and tensions grew. In the following days, several confrontations with U.S. and Mexican border agents occurred as groups attempted to cross at the official port of entry in San Ysidro and at the ocean border wall.

In subsequent years, due in part to the threat of withheld aid funds, Guatemala and Mexico increased their enforcement policies and turned back migrant caravans. A December 2020 caravan that left San Pedro Sula was stopped before entering Guatemala. “When Trump said he was going to make Mexico pay for the border wall, people thought it was going to be a physical wall between the U.S. and Mexico,” Rivera says. “But what he effectively did with these policies is force Mexico to build a wall—a human wall of military presence—along its southern border with Guatemala.”

In opposition, the Biden campaign published materials such as “The Biden Plan for Securing Our Values as a Nation of Immigrants.” In this and related documents, the new administration proposed dismantling punitive Trump-era policies levied under the guise of a national emergency, including family separation and detention, an intentionally slow asylum system, and the reduction of asylum quotas. In their place was a commitment to partner with humanitarian and faith-based groups to provide assistance to those approaching the U.S. border, an end to prolonged detention, and removal of travel bans that targeted those seeking legal entry into the U.S. from predominately Muslim countries and asylum seekers. Additionally, the Biden campaign promised to extend naturalization opportunities for green card holders and young people without documentation who were brought to the U.S. as children. In practice, however, the Biden administration has taken a hard line against people entering the U.S. unlawfully: In February 2021, 72 percent of those crossing improperly and encountered by the Border Patrol were sent back to Mexico or expelled to their home countries.

The Biden campaign proposed a $4 billion regional strategy to address factors in Central America that power migration, mobilize private investment, improve regional security, address corruption, and prioritize poverty reduction and economic development. The day President Biden took office he introduced the U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021 in which he outlined the goals of this financial aid with the hope of addressing the root causes of migration by “increasing assistance to El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, conditioned on their ability to reduce the endemic corruption, violence, and poverty that causes people to flee their home countries.”

At a March 10 press conference, Roberta Jacobson, former ambassador to Mexico and a senior adviser to Biden on border issues, said the administration had heard the concerns of some legislators and was taking a cautious approach to distributing the proposed aid to government entities. “I want to emphasize that the funds we’re asking for from Congress don’t go to government leaders; they go to communities, to training, to climate mitigation, to violence prevention, to anti-gang programs,” Jacobson said. “In other words, they go to the people who otherwise migrate in search of hope.”

But for many, these policy changes don’t yet fully address the critical needs of everyday people in the Northern Triangle. “When you lose hope, when you realize that what happens [politically] doesn’t matter, that things are not going to change,” Rivera says, “then the only logical path is to leave and not return.”

‟If people felt safe, if they felt provided for, if they had opportunities for education and to educate their children, they would not leave.”

La Terminal

A SECOND 2021 migrant caravan was announced via social media shortly after the Jan. 15 caravan had reached Guatemala. Urged on by Facebook groups and WhatsApp chats, approximately 75 people gathered in the humid early evening hours of Jan. 24—before the 8 p.m. COVID-19 curfew—at the San Pedro Sula bus terminal, known locally as La Terminal, in anticipation of joining the caravan the next morning.

Bolstered by what they perceived as success in the previous caravan’s progress, this seed group had arrived on buses from around Honduras and waited for others to fill their ranks. Unfortunately for them, law enforcement and others determined to stop or apprehend caravan participants had also been monitoring social media. Before more people could gather at La Terminal as they had 10 days prior, a detachment of military police dressed in riot gear arrived in an armored vehicle. Joined by local police, they dispersed those gathered—families, groups of young men, a few individuals—and word quickly spread on the WhatsApp group chats urging others to stay away.

Before the police arrived, Rivera Hernandez sat on a median in the parking lot of La Terminal with his wife, Lorena, and his pre-teen son Jason, waiting for the caravan to assemble. The family traveled

from the hurricane-ravaged town of La Lima, just outside San Pedro Sula. He spoke openly about his plan to go to the U.S. It’s the family’s first migration attempt. He said he’s heard things have changed and the United States is letting people seek asylum now that Biden is in charge. When asked where they will go in the U.S., or how they will get there, he’s less certain.

“We will just go north with the caravan, but we don’t know the route,” he said of their itinerary. “We will wander aimlessly (deambularemos sin rumbo) until we get there. Nobody is waiting for us.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!